"Let us rise up and be thankful, for if we didn't learn a lot today, at least we learned a little, and if we didn't learn a little, at least we didn't get sick, and if we got sick, at least we didn't die, so let us all be thankful." Buddhist quote

“Beneath the twinkling stars I anxiously strain to scan the dark sea in front as our tiny aluminium fizz boat motors up and over the Pacific Ocean waves… I know that somewhere out there where the waves are smashing against the reef lies a merciful gap through the razor-sharp coral outcrops… that we must find if we are ever going to make it through to the safety of the tranquil atoll lagoon.”

In 1980 after working at Craig McLeod's sound postproduction studio for a year in Auckland, New Zealand I took the plunge and a huge gamble… and gave up the security of a regular weekly paycheque for the uncertain up and down rollercoaster life of working as a freelance sound recordist!

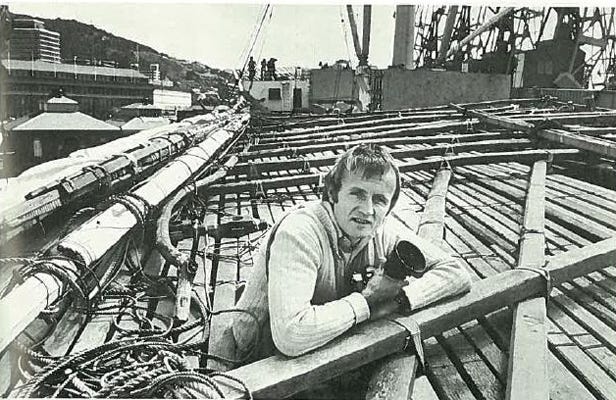

I was soon approached by James Siers of Sierpinski Films to work on his documentary up in Kiribati in the Pacific about 3⁰ South of the equator.

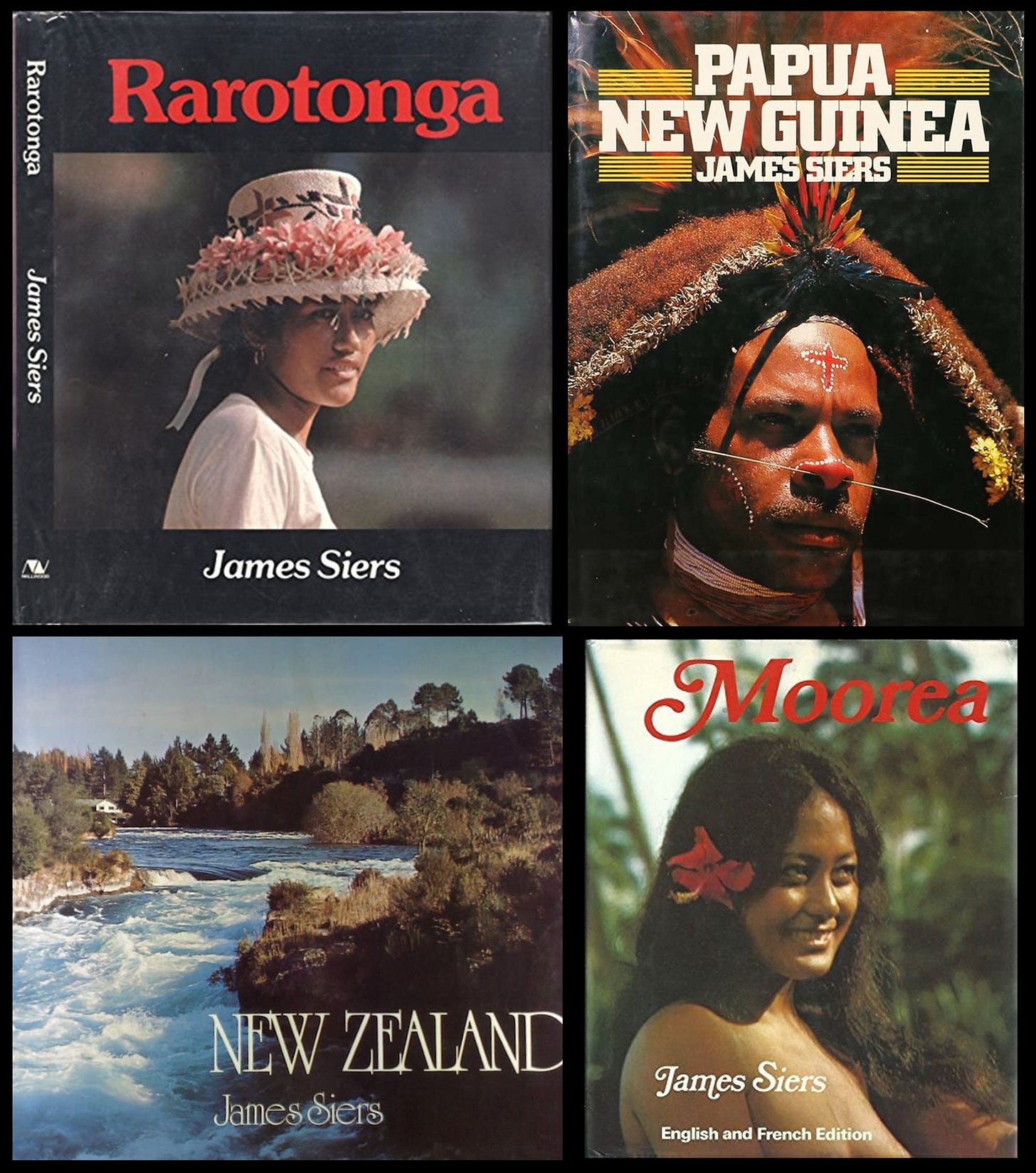

James Siers

Jim is an interesting character… a photographer, author, publisher, documentary filmmaker and Pacific adventurer. Back then he went on adventures in the Pacific taking lots of gorgeous photographs, then sent them back to his wife Judy in Wellington who published them in beautiful coffee table books via their own publishing company Millwood Press.

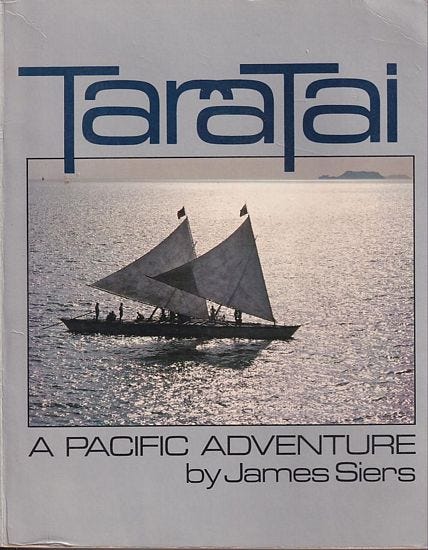

In 1977 Jim made an incredible 1500-mile voyage from Kiribati’s main island of Tarawa to Fiji in a traditional outrigger canoe that he had built.

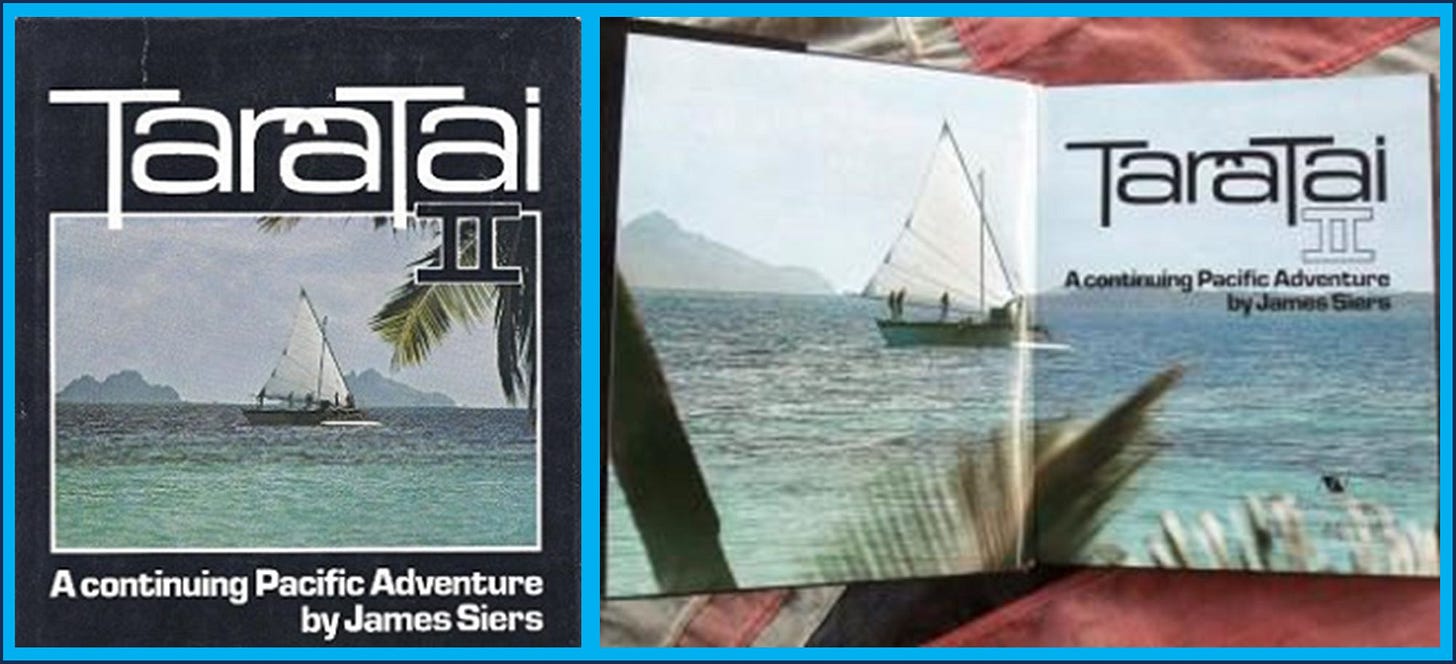

A while later he embarked on another epic voyage, from Fiji to New Zealand in a new modern outrigger canoe, that ended in near-tragedy when they got hit by a rogue wave near Niue which snapped off the outrigger float, and the mast broke.

Jim with his 10-year-old son Conrad and his five Gilbertese Islander crew then spent two weeks drifting in a leaking life raft before finally being rescued. During that ordeal Jim made a promise to 40 year old Tarabo Teem, one of the crew who had a son the same age, that if they were rescued, he would send Conrad to spend time with his Gilbertese friend and his family in Kiribati to learn some of the Gilbertese ways of living.

So, 3 years later, here I find myself on a jet with cameraman Ian Paul flying from New Zealand to Kiribati to work on Jim’s planned documentary EYE OF THE OCTOPUS about Conrad’s experiences learning the Gilbertese ways of living.

We chat about how we are going to approach the project. Jim previously had a film crew shooting this documentary but a Christchurch cameraman had apparently gone ‘a bit troppo’ in the heat and would wake up and say “I do not feel creative today…“ so he wouldn't go out and shoot anything.

As the replacement crew hired to complete this doco we want to avoid the same thing happening to us, so we make a pact to launch straightaway into the filming, and to be wary of going ‘troppo’ on that hot Pacific Island that we are jetting towards, almost on the equator.

When we land at Bonriki airport on Tarawa, the main island of Kiribati, Jim is there to meet us, along with Alan, his very suntanned Kiwi boat driver/assistant.

We head down to the nearby harbour and load all out film and sound gear into a 16-foot Fyran aluminium open decked fizz boat, and we motor off across the lagoon as night gently lowers its warm tropical coat upon us.

Similar size to this Fyran but without the blue cover

I look behind me at the slowly fading lights of Bonriki, and then with trepidation at the blackness of the sea ahead of our tiny, vulnerable craft. I gaze in wonder at the amazing twinkling stars overhead.

As we pass the only visible navigation light our boat begins to rise and fall over the waves as I soon realise “Crikey… we’ve left the calm atoll lagoon behind and now I’m in the open sea! … in darkness… with 2 complete strangers… and no navigation lights ahead of us… in a tiny open-decked metal boat with our many cases of expensive camera and sound gear… am I crazy for agreeing to take this sound job?”

I realize that I just have to trust that Jim and Alan are experienced and know what they are doing.

Alan stares fixedly ahead watching and waiting for the glimmers of white foam that indicate where the waves are smashing on the reef surrounding the atoll that we are heading towards.

I hear the roar of the surf as he spots the breaking waves, turning the boat to run parallel to the reef… searching ahead for the illusive calmer stretch of water that signifies the tiny gap through the razor-sharp coral outcrops. Finally, we zoom through that minute opening… into the welcoming embrace of the tranquil atoll lagoon.

A short sprint across the calm waters brings us to the tiny island of Ribono, my home for the next few weeks.

Ribono is about ¾ mile long, by about ¼ mile wide, has no power, no running water, no sewage system, no shops, no roads, no vehicles… just a very basic lifestyle that I soon sink into.

There is one village, and Jim has a traditional native hut for me and Ian to stay in set in a small group of his huts a short walk away.

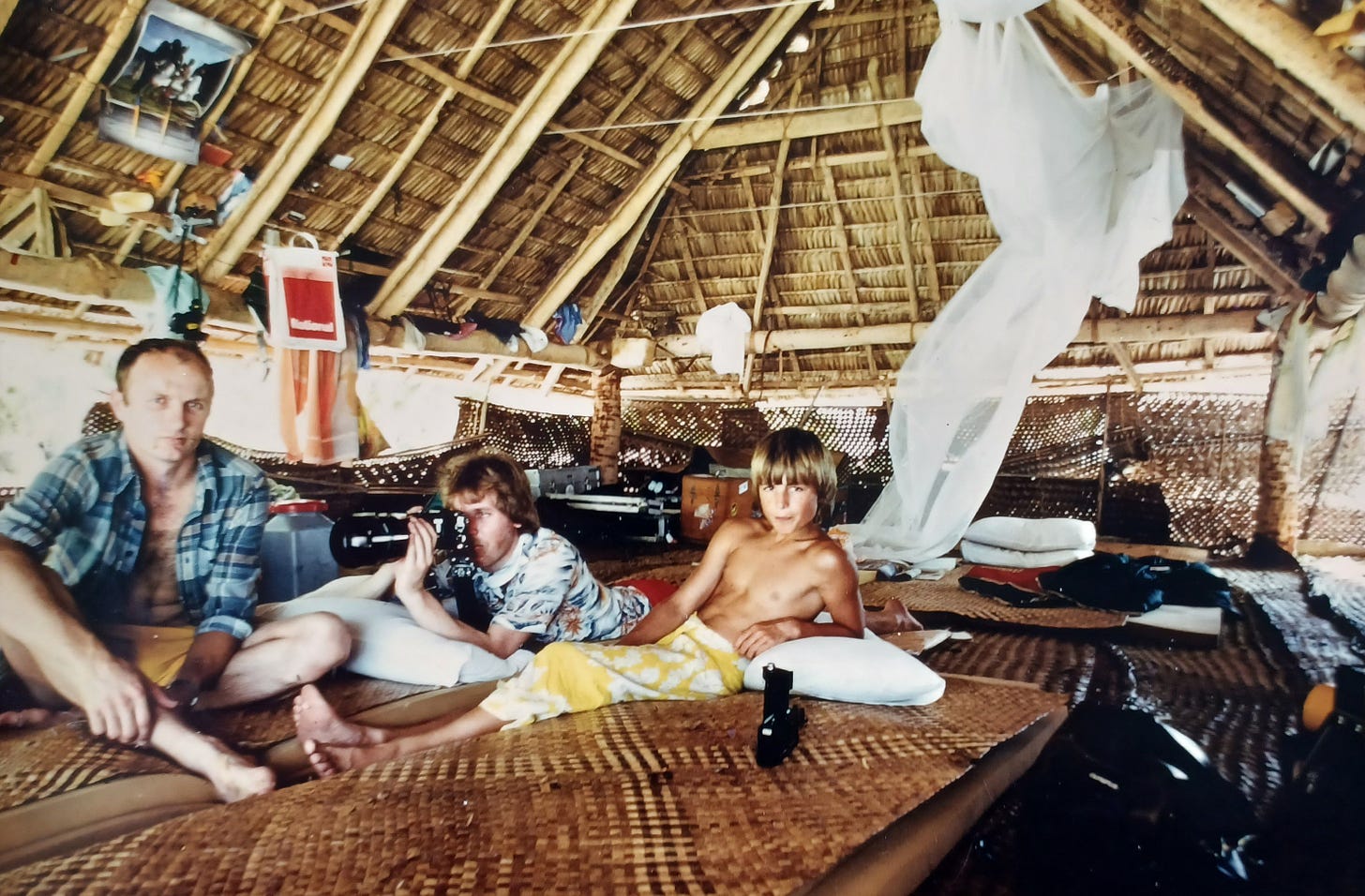

Myself, cameraman Ian & 13 year old Conrad

My bed is a foam squab set on a traditional woven floor mat with a mosquito net over it and a spray can to use each night to ward off the mozzies. There’s a kerosene fridge nearby to keep our precious filmstock cool. These are the days before digital cameras, before video cameras, even before mobile phones and computers, at a time when all the documentaries are shot on 16mm film stock.

Jim has arranged for a different local family to cook dinner for us each day. And he explains that our ‘toilet’ is “A 50m section of that beach you can just see there through the trees… between a large fallen coconut tree and the distinctive rocky outcrop you’ll notice when you go there to use it for the first time… just dig a shallow hole in the sand… but when you’re finished make sure you cover it up so the big crabs don’t get at it” …charming!

Our first morning on Ribono Jim says “Let’s go down to the maneaba (meeting house) and I'll introduce you to the village”. Ian and I look at each other… ‘Shall we take the gear?... Yeah, let’s do that”.

So, we stroll through the coconut trees down to the huge maneaba where the whole village is gathered to meet us.

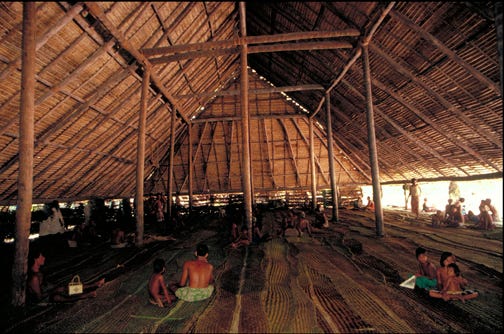

Maneaba (meeting house) similar to this one

Jim introduces us to the villagers… and then we start filming, and filming, and filming… for 14 days straight! No way are we going to risk going troppo!

We film 13-year-old Conrad and his same age Gilbertese ‘guide’ teaching him how to face a number of tests of courage; first he has to learn to climb a tall coconut palm to get the ripe coconuts (islanders sometimes get killed when hit by these heavy falling coconuts).

Then he has to master a traditional outrigger canoe built specially for him.

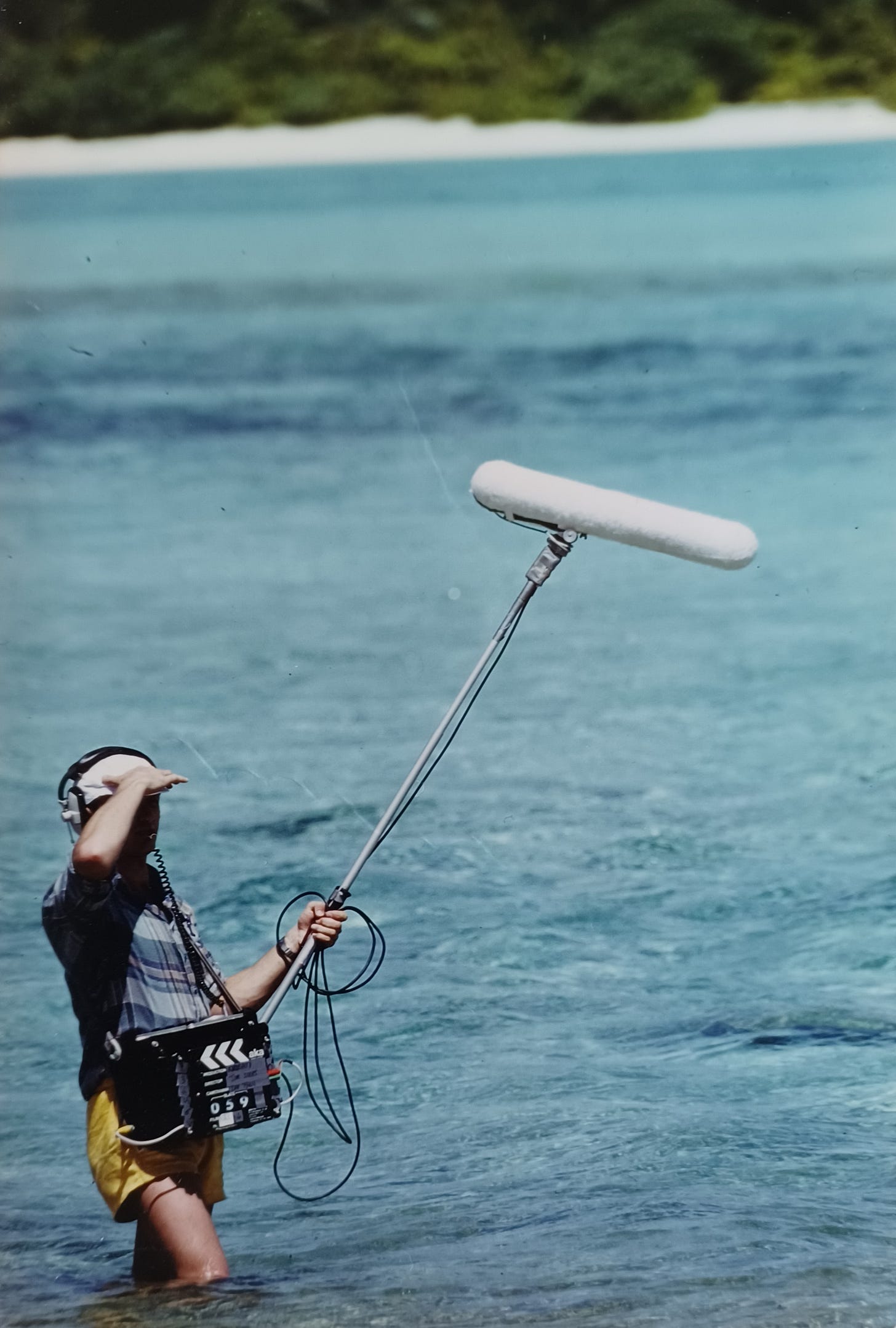

Myself and Ian filming outrigger sequence

Jim took all these photos of us working

Next Conrad has to catch fish at low tide while running across the shallow reef.

Assistant Alan, me & Ian

Then he has to learn skindiving - not only in the sheltered lagoon but also in the ocean, within sight of sharks and over colourful but deadly coral reefs.

Then comes the toughest test of all. He has to catch an octopus, an animal whose tentacles are strong enough to kill a grown man, and kill it by the traditional island method: biting it between the eyes! This sequence is to be filmed later with a specialist underwater cameraman.

Shark fishing sequence outside the reef in the open ocean

The shooting days are incredibly hot. I drink endless cups of hot tea… yes hot tea because it makes me sweat, and the sweat cools my skin. When we are filming amongst the coconut palms, we ask Conrad’s Gilbertese friend to please get us some fresh coconut milk to drink.

He kindly scurries up the nearest coconut palm in no time at all, knocks down one coconut each, climbs down, deftly slices the head off my coconut with his sharp machete, then I drink the totally refreshing cool, slightly milky and ohh so satisfying coconut juice… until my stomach is satisfied… ahhh… bliss!

I must tell you that going to the toilet each day is quite a challenge for city slicker me. It’s a little confronting having to find a yet unused section of our ‘beach toilet’, dig a hole and then squat Asian style to ‘do my business’.

The upside is I can often watch a glorious tropical sunrise across the blue water in front of this beautiful beach that I have all to myself. The downside is I feel incredibly vulnerable in my nether regions, as I’m constantly on guard looking for those large, scuttling land crabs that could seriously threaten my dangling crown jewels. It doesn’t make for a relaxing daily experience!

The Gilbertese are staunch Catholics, and one day I wake up to hear the news that one of the islanders has died, and Jim says that we need to do the right thing and go down to the maneaba to pay our respects to the grieving father.

Maneaba like this one

The young man's well-dressed body is laid out in the maneaba and covered with brilliantly colourful, aromatic flowers because on this tropical island where there is no refrigeration a dead body decays very quickly. His grieving father, dressed in his best shirt and long trousers, is sitting tear-stained beside his dead son. Villagers are gathered around as we also pay our respects.

What really strikes me is that around the edges of the maneaba which has open sides, the village kids are playing, dogs are running, and life goes on. The wonderful never ending circle of life is right here in front of me in this village where death is treated as very much part of the ongoing life of the village, not hidden away as something separate as it often is in modern Western society.

I hear that this young man committed suicide. He was in love with his brother’s wife and in a strong catholic society he knew he couldn’t do anything about it, so in despair he hung himself, in front of his brother’s house. So sad. In Catholicism suicide is a mortal sin and someone who commits suicide can’t be buried in consecrated ground, so that created a dilemma for the village priest. I’m glad to say this was eventually resolved and the young man was indeed laid to rest in the village’s church graveyard.

Working on this documentary I learned a lot about life, death, myself, compassion, and gratitude.

I also learned never to take the important people in my life for granted… so I try to use those incredibly important words “I love you’… every day.

Day 16 Boadilla del Camino to Carrion de los Condes 4 June 2018 24.5 kms (15.2 miles)

I leave at 6.00 am - too dark to see the yellow arrow markers. I fire up my Camino Frances map app, zoom into where I am right now and sort out which branch of 3 forks to take... then I'm on track.

I think I'll wait until it's a bit lighter in future.

I stroll along beside the Canal de Castilla to Fromista, accompanied by an orchestral croaking from the frogs and toads amongst the reeds bordering the canal.

At 9 kms I stop for breakfast at a small town, Población de Campos.

The land is very flat and not particularly engrossing. The track runs beside the highway for the rest of the day.

I catch up with Ray from Melbourne and we enjoy a lovely chat as we walk the 11 kms to Carrion de los Condes.

He tells me about losing his severely handicapped son Luke at the young age of 13.

Ray

We discuss God, and Ray talks about how his only daughter is a firm atheist, yet he tells me a poignant story about the day his son died.

Surrounded by family they finally turned off his life support system, and the doctor said it could take an hour or two before Luke would pass away. Apparently his only sister was the light that brightened up Luke's day whenever they were together.

Ray said his daughter couldn't stay in the room with all the family gathered around his son's bed, but waited outside the room.

Then suddenly, there she was at the doorway saying "I'd like some time alone with Luke". So the family all left the room... she leaned over her brother's bed and whispered something in his ear. And to this day she has never told Ray, her dad, what she said to her brother.

Fifteen minutes later Luke passed away.

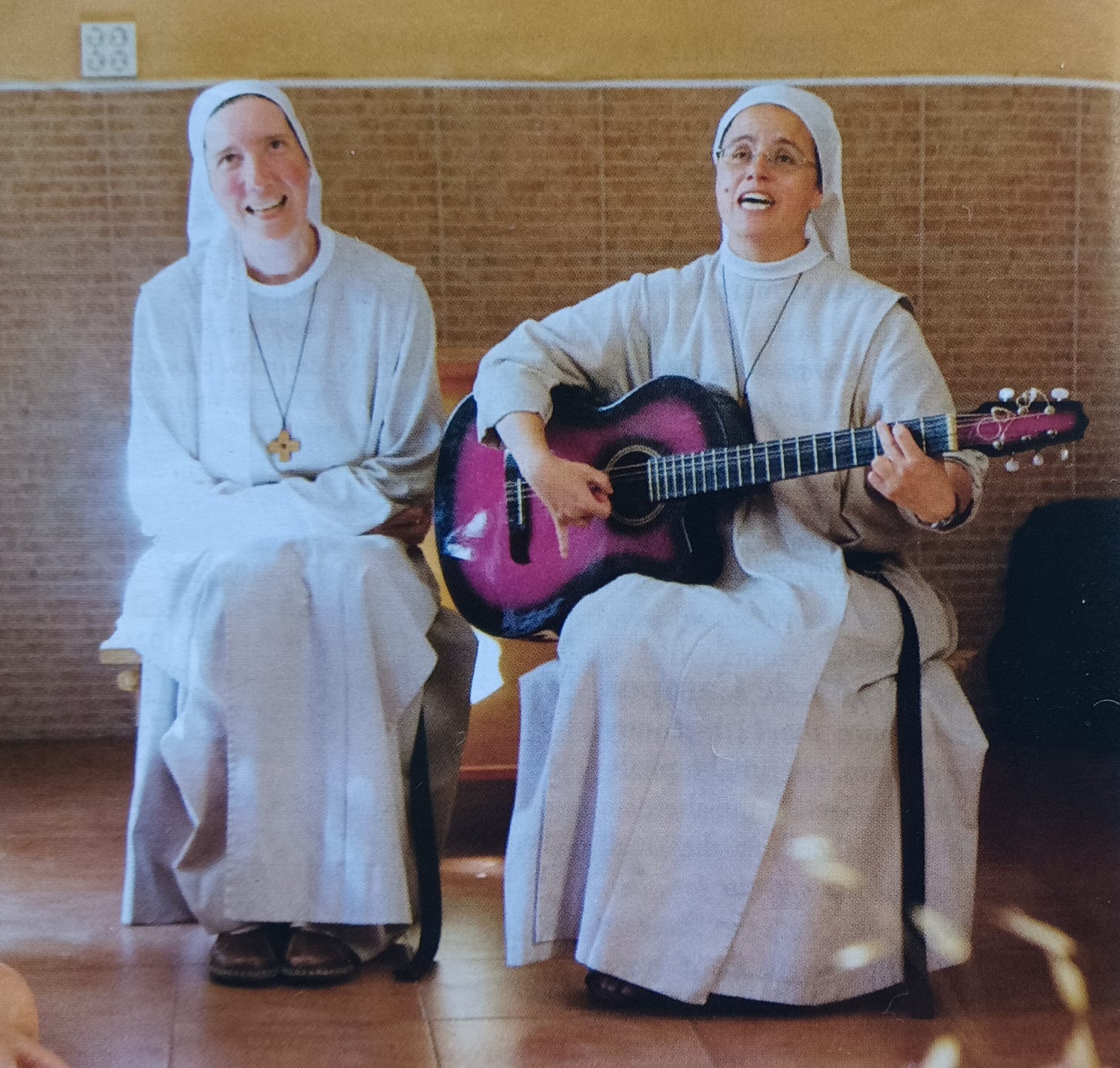

We finally arrive in Carrion de los Condes and check into the Santa Maria albergue, run by nuns attached to the Iglesia de Santiago (church of Santiago).

The nuns organise a fun nightly sing along session with the peregrinos from many countries - a lovely chance to sing both familiar and new songs.

I eat a delicious meal, then climb into my bunk bed and settle down to sleep... in a dorm of 16 other, hopefully, non-snorers.

My learning for today:

Everybody has a story to tell, and if you give that person the time and attention, some heartfelt revelations will often be shared.

I hope you all have had a wonderful Christmas surrounded by family and friends, and I wish you all a fun, exciting, peaceful, joyful and loving 2024.

Goodnight, and much love and gratitude from New Zealand.

Dear Hammond, I very much love your way of taking us through your experience: the life experience and the Camino experience. Looking forward to day 17. Love to you and Renata!